ON 9 NOVEMBER 1991, music enthusiasts and curiosos gathered at the South Park Community Center in Seattle, Washington, US. Some had travelled from as far as San Francisco, California, more than 1,000 km away, most were American, and all had paid between $25 and $35 to partake in a celebration of traditional Zimbabwean music at the inaugural Northwest Marimbafest.

The day-long festivities included a conference, performances by Seattle-based groups like the Mahonyera Mbira Ensemble and Anzanga Marimba & Dance Ensemble, and workshops on how to play traditional Zimbabwean instruments. It was a small affair, but the community banded together to make it happen, some locals even opening their homes to out-of-town visitors.

For years prior, mbira and marimba music had been burgeoning in the western US thanks in large part to famed musician Dumisani Maraire, who had taught it in schools in the region and had founded mbira and marimba groups. In fact, at the heart of organising the first Northwest Marimbafest were a handful of American students who had trained under Maraire at some point and had been touched by the music.

One of them, Claire Jones, first heard traditional Zimbabwean music at a performance in 1976, and the experience changed her life.

“This is the music for me,” she thought to herself.

Jones would later make Maraire's acquaintance while pursuing a master’s degree in science education at the University of Washington and would travel to Zimbabwe right after Independence as part of Maraire’s marimba ensemble. She once confessed to Maraire, “This is the music I’ve been waiting for all my life,” and she wasn’t alone in feeling that way.

Over time, her love for and knowledge of traditional Zimbabwean music only crescendoed.

“There's an inherent joy,” Jones said of what drew her to Zimbabwean music. “There's also a depth of spirituality, especially with the mbira music, and you can get it with the marimba music, too. And it's very communal.”

Upon returning to the US, following a five-year stint teaching in Harare first at Cranborne Boys’ High School and then at Oriel Girls High School, she and her peers would put together the Northwest Marimbafest. They couldn’t have known the festival would continue to be a beloved hub for cultural music in the Pacific Northwest for over three decades.

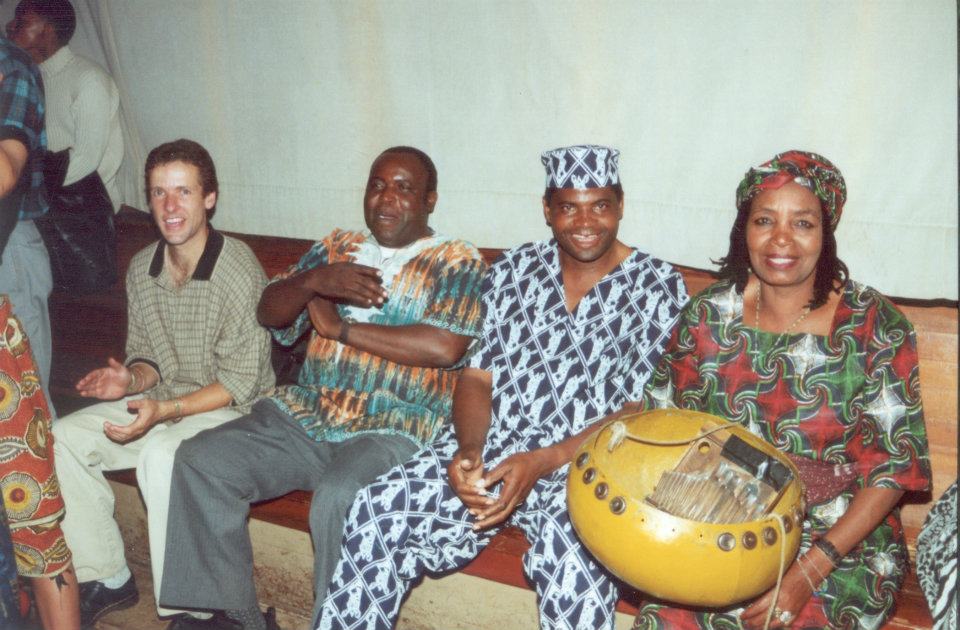

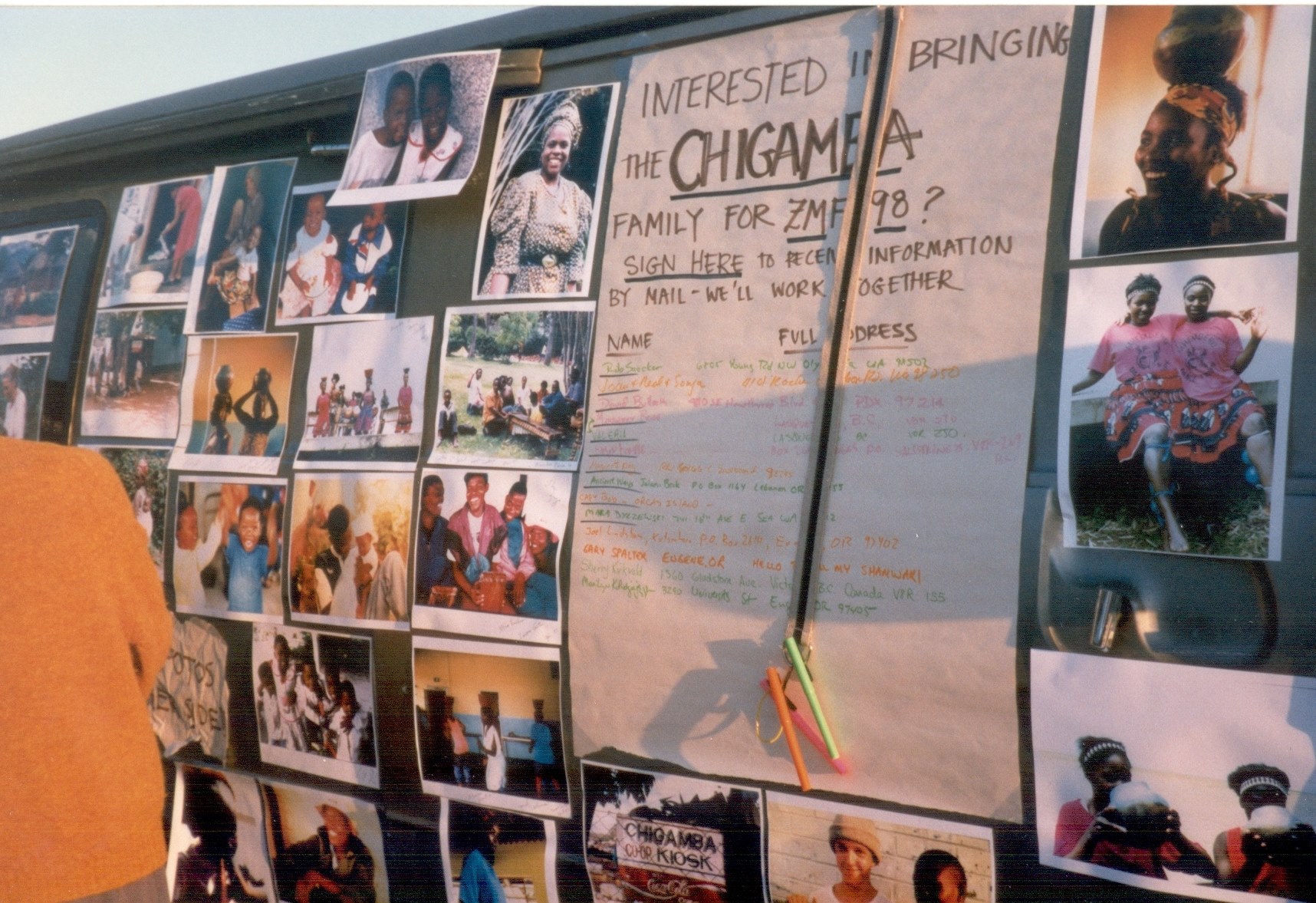

Now known as the Zimbabwean Music Festival, Zimfest for short — the name changed in the early years to include other forms of music — it has attracted big-name guests and performers over the years like Irene Chigamba, Cosmos Magaya, Stella Chiweshe, Mbuya Beauler Dyoko, Sheasby Matiure and, of course, Maraire, Lora Chiorah-Dye and their son Tendai Maraire.

Very quickly, the event became a cultural mainstay, serving an unlikely community made up of Zimbabwean and American lovers and practitioners of traditional music.

In the years following Independence in 1980, this community held annual celebrations on 18 April to commemorate the day. From these, Zimfest was born “to continue to have a gathering of people who were already enthusiastic about the music, and to be a place to continue spreading the music,” said Jones, the festival coordinator and an ethnomusicologist.

And spread it has. Since its founding, Zimfest has travelled throughout the western US, making stops at cultural centres, universities and parks in California, Oregon, Colorado, Idaho, and even outside the US in Canada, drawing hundreds of guests each year for a weekend of festivities. Until recently, Zimfest was an annual concert, but it has since switched to a biennial model, alternating years with another similar music festival in Canada. This year, Zimfest will take place from 7 to 10 August at Central Washington University and will return in 2027.

Unlike many large musical events, Zimfest is a “teaching festival,” Jones said, meaning its focus is to educate guests on the traditions of Zimbabwean song, dance and culture, which once included serving Zimbabwean food but is now mainly achieved through dozens of workshops. At this next instalment, Zimbabwean and American instructors will teach participants about Ndebele singing, the basics of playing hosho, storytelling through ngano, and more. From a small, one-day programme in 1991 to 80 workshops and nearly 30 performances this year, Zimfest has expanded and maintained its offerings, despite a lack of reliable funding and post-pandemic growing pains.

So, how did a music tradition from a country thousands of kilometres away take root in a region in the US that couldn’t be more different, culturally speaking? How did the otherworldly timbre of mbira, the upbeat rhythms of marimba, the pulsating depth of ngoma, the sweet sounds of chipendani or the hypnotic rattling of hosho appeal to so many?

Tendai Muparutsa, a musician, lecturer at Williams College in Massachusetts, US, and ethnomusicologist, attributes it to the inherent curiosity of Americans.

“They are not afraid to try new things,” he said. “And our music is not for everybody. There's some people who don't like it. It’s normal. But to those people who like it, they find the spirituality, especially in the mbira…They sit under a tree, and they play, and they get connected somehow with it.”

Born and raised in Mutare, Muparutsa’s musical career was essentially fated. His father, aunts and uncles made up the Runn Family, a mbira-centric band that gained notable recognition in the 1980s. As a child, Muparutsa didn’t find band life appealing. There was no escaping it, though. He was constantly surrounded by his relatives’ instruments.

Years later, Muparutsa travelled to the US to pursue a master’s degree in music education at the University of Idaho, where he also played in the school’s marimba ensemble. It was there that he crossed paths with Jones, who invited him to teach at Zimfest, and he accepted the offer, leading mbira and marimba workshops for a few years. Although Muparutsa no longer teaches at Zimfest, he makes it a point to attend when he can and is now a board member of the Zimfest Association, the festival’s nonprofit managing organisation.

As an academic in music, Muparutsa, who co-directs Kusika and the Zambezi Marimba Band, finds great value in the networking opportunities he gets from attending Zimfest, but the “joy of playing music from the country” is unlike anything else, especially for Zimbabweans based in the US. “We are foreigners here. We live out here, and you hardly ever hear that kind of music played on any radio station…For those four days that we are together at Zimfest…we go and then get enmeshed, engrossed, and we enjoy ourselves,” he said. It satisfies nostalgic cravings.

IN THE EARLY YEARS of Zimfest, the attendance was largely American, and so were the teachers. While the demographic remains the same among the guests, Jones and the Zimfest Association have made it a priority for the past decade to encourage more Zimbabweans to be on the board. “They do lend a perspective that us Americans don’t have,” Jones said. The same goes for the roster of teachers, which now includes more Zimbabweans than it did historically. Half of this year’s 23 workshop leaders are Zimbabwean.

In many ways, Zimfest is a paradigm of cultural exchange. The festival was started by students of a Zimbabwean artist who generously shared his knowledge of traditional music, and it has been preserved by a mix of Zimbabwean and American patrons of the art form. However, both Jones and Muparutsa said the festival has occasionally been the subject of allegations of cultural appropriation, going back as far as its founding.

“I would like to dismiss that criticism,” Muparutsa said, noting that while he knows of people who have lodged these critiques, “I haven’t seen a great many.” He continued, “We always find a lot of Zimbabweans who are not into the music, but they come to the performances, and they enjoy the performances.”

Zimfest, Muparutsa said, has played a key role in the proliferation of Zimbabwean music beyond the Pacific Northwest. There are several mbira and marimba bands in the US, including in states like Alaska, New York and Maine.

Jones experienced the pushback firsthand. When she lived in Zimbabwe, locals welcomed her curiosity about traditional music and her ability to play it. In the US, it was often a different story. She gets where the scepticism comes from, particularly when there has been a recorded history of appropriation of Indigenous American cultures and traditions by white Americans. She wants to prevent that.

“Part of my mission within Zimfest is for all of us white people to understand that at the beginning of the day and the end of the day, we are still not of this culture, and we need to cultivate that understanding,” she said. “And with the young people that are coming up, they need to become aware of that too.” She continued, “This is music coming from within a centuries-old culture which, no matter how much we study and immerse ourselves, we don't totally understand.”

A correction was made on 30 July 2025: An earlier version of this story misstated the relationship between Dumisani Maraire and Lora Chiorah-Dye. They were not married.