ON THE CHILLY Friday night of 23 November 1984, Fred Zindi was in a sardine-packed crowd at the 100 Club, a live music venue in London, waiting for the performance to begin.

“We were excited because this is the first time a Zimbabwean musician [came] to the UK,” said Zindi, a musician and a professor at the University of Zimbabwe.

It wasn’t just any Zimbabwean musician, though; it was Thomas Mapfumo, whose activism and musicianship had put him in a class of distinctly well-loved artists and who had just completed a successful tour in Africa and Western Europe with his band, The Blacks Unlimited. The 100 Club’s capacity was about 300 people. But with all the excitement, the attendance far exceeded the limit, Zindi recalled, with concert-goers eager to see a legend in the flesh.

While the other patrons experienced Mapfumo only from a distance — he performed in a sequined army uniform accented by a multicoloured hat — Zindi, then a student at the University of London, obtained unique access to the star. Zindi wanted to expand on his previous coverage of Mapfumo, which he had written as a columnist for Moto, a Gweru-based publication, so he approached the musician and told him as much. The following day, Zindi would visit Mapfumo at his hotel, where he would interview the icon for about four hours and again over the following two weeks. The extensive notes Zindi took during the no-doubt transformative conversations would form the basis of a book he would write during his school holidays.

Published in 1985 by Mambo Press, the book, “Roots Rocking in Zimbabwe,” chronicles in great detail the state of music in Zimbabwe until the early 1980s, tracing the path of traditional music into the mainstream, the international influences that shaped music of that time, and what it meant to be a musician under colonial rule.

In the book, Zindi also recounts that momentous night he watched Mapfumo perform in London: “Everyone had gone into a frenzy, everyone had danced to the music, everyone had enjoyed the concert and Thomas's magic had brought everyone in the packed club into an [indescribable] emotional state of ‘feeling good.’”

Just as Zindi drew inspiration from Mapfumo’s words, 10 years later, Samy Ben Redjeb, founder of the Germany-based company Analog Africa that unearths and reissues African records from the past, would find inspiration in Zindi’s writing and, 30 years later, revive Zindi’s book — and the rich musical history contained within it.

In May, Analog Africa released a compilation album titled “Roots Rocking Zimbabwe: The Modern Sound of Harare Townships 1975-1980”, named after Zindi’s book. The record features 25 tracks by musicians who dominated the industry during the tail end of colonial Zimbabwe, the likes of Mapfumo, Oliver Mtukudzi and The Black Spirits, electronic group New Tutenkhamen, and psychedelic rock band Baked Beans, some of whom were discovered or first recorded by drummer and producer Crispen Matema. Along with the album and its booklet, Analog Africa also published a new edition of Zindi’s book, which has been out of circulation since 1990.

The year 1975 marked the beginning of Zimbabwe’s music industry, and the album demonstrates the styles that reigned. The exciting blend of traditional Zimbabwean music, funk, jazz, rock, soul and reggae formed the distinct sound generically referred to as “township music,” which emerged in a tense political climate. White colonialists, particularly missionaries, vilified traditional music played on mbira and ngoma, for example, deeming it unholy or pagan. Faced with this denigration and a commercialising sector, Black Zimbabweans began incorporating international styles into their craft.

This “township music” is at the heart of “Roots Rocking Zimbabwe,” and its moulding and remoulding of genre is unambiguous in each track. Also embedded in the LP is the political discourse of the time, as in Dagger Rock Band’s “Viva Zimbabwe,” a punchy rock track about the country’s years under colonial rule, and Mapfumo’s “Chiiko Chinotinetsa,” a number whose buoyancy disguises the socio-economic plights the musician sings about. And then there are tracks like Baked Beans’ “Introduction,” just a groovy three minutes of a band’s role call, and “Engelina” by Echoes Limited, whose Latin influences make for a bouncy, danceable tune.

Every song on the compilation holds a uniquely raw sound that lends it the quality of being played in real-time in a thrilling bar or a cosy concert space like the 100 Club.

Ben Redjeb said the selection of songs was informed by a desire to cater to as many tastes as possible. Of course, he also included some personal favourites like the two songs by The Green Arrows. (The band holds a special place in Ben Redjeb’s heart, having been the focus of Analog Africa’s first release.)

“In this compilation, there is not a single song that I don't like,” Ben Redjeb said of “Roots Rocking Zimbabwe,” in an interview with Landlocked. The years represented in the record were some of the most magical, with “all these bands crisscrossing Zimbabwe, playing in clubs,” he said. “There was such an energy in the country,” he recalled famed guitarist Jonah Sithole telling him. This inimitable electric charge is palpable in the album.

Ben Redjeb first encountered Zimbabwean music in 1995 while working as a DJ in Senegal. A year later, in 1996, he travelled to Zimbabwe, where he discovered Zindi’s “Roots Rocking Zimbabwe” in a bookstore. As a music enthusiast, Ben Redjeb was struck by the book’s contents — its in-depth interviews with Mapfumo and Mtukudzi, two of the biggest names on the scene at the time, and its nuanced representation of the music.

It became a sort of bible and “opened up a whole new world to me, making it much easier to understand the music scene I was so eager to explore,” Ben Redjeb writes in a blurb.

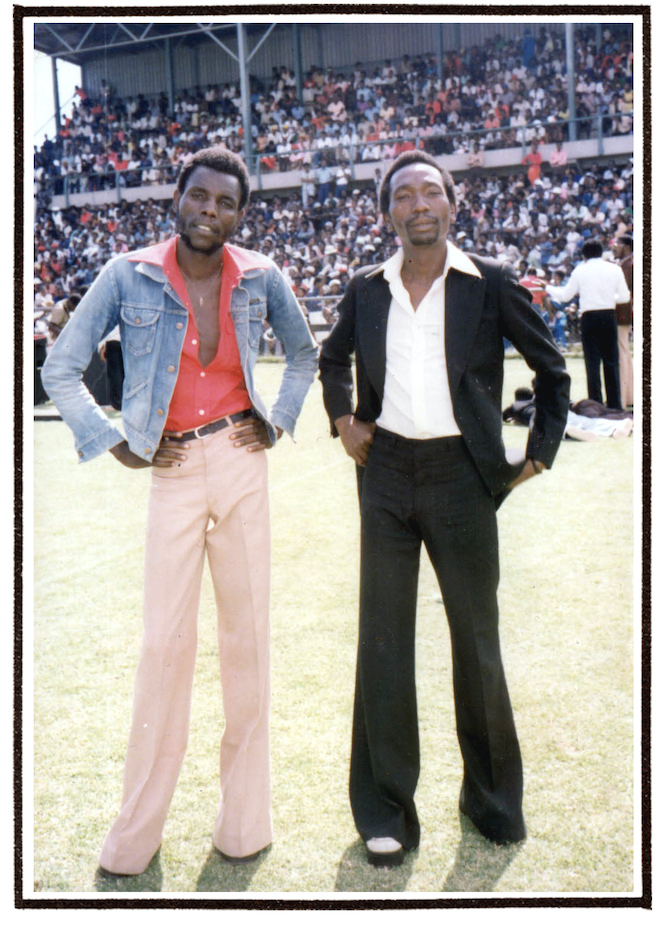

Years later, while working on “Roots Rocking Zimbabwe,” Ben Redjeb travelled back to Zimbabwe, where he asked Zindi if he could name the compilation after his book and republish the work to accompany the LP. Zindi accepted, requesting a $200 fee and half of the book’s profits. The new edition of Zindi’s book, available for sale online, includes more photos — over 100 from Zindi and Ben Redjeb’s collections and magazines — and features The Green Arrows on its cover instead of Mapfumo, who graces the 1985 edition. Apart from a few editorial tweaks, the written content remains largely the same.

In the introductory chapters of his book, Zindi traces the breakthrough of traditional music into the mainstream until the 1950s, supported by the Rhodesian Broadcasting Corporation, which would send a van around town to record songs on a one-track tape recorder for its African Service radio broadcasts. In 1956, Zindi writes, traditional music began to fade from popularity as South African, American and European tracks took over. Around this time, local corporations like the British manufacturing company Lever Brothers began tapping African musicians for marketing purposes, offering sponsorship in return. A jingle for Sunlight dishwashing liquid, for example, became a hit, and the cover for the 2025 re-edition of Zindi’s book is an advertisement that appeared in Parade Magazine for the shoe retailer Bata.

While most musicians steered clear of political content in the charged climate of mounting anti-colonial resistance, traditional music experienced a revival in the 1960s and ‘70s in the form of Chimurenga music, which critiqued white rule and spurred on the revolution, like Mapfumo’s 1976 album “Hokoyo!” Still, the popular music of the time combined traditional rhythms with American, European, Caribbean and broader African styles.

Zindi spends the bulk of his book painting portraits of 15 musicians and bands representative of the zeitgeist, generating a treasure trove as far as music history goes, with photos of musicians playing on stage or going about their days, including one of Zexie Manatsa of The Green Arrows on his wedding day alongside his bride. The chapter on Mapfumo, derived from Zindi’s in-depth interviews, is made up of seemingly unsynthesised and often mundane nuggets from his life: his upbringing in Marondera, the all-night drumming at his grandfather’s parties and his early musical career as the lead singer for a band in Mabvuku called Mazutu Brothers.

Also featured in the book are interviews with Mtukudzi, Susan Mapfumo and Lovemore Majaivana, as well as short biographies of Manatsa, the Harare Mambo Band and Nyami Nyami Sounds. Zindi’s book highlights mostly male singers, the demographic that prevailed at the time (Joyce Jenje-Makwenda’s 2005 book “Zimbabwe Township Music” offers a rich look into the women musicians of this era.)

During the industry’s early days, Black Zimbabwean musicians lacked the equipment to perform in large arenas. Many of the artists featured on the “Roots Rocking Zimbabwe” compilation didn’t even own their instruments, Ben Redjeb said. “For them to basically have these instruments from time to time…but then play as [well] as they did simply means that they were extraordinary musicians.”

Zindi concludes his book with a look towards the future amidst growing international recognition of African music. “Now is the time for all good Zimbabwean bands to make their mark and sell their country to the rest of the world for the future is bright, but alas, charity begins at home,” he writes. “I look forward to the day when Zimbabwean musicians will receive awards from the government and record companies for their outstanding work,” he continues.

So much has changed since the 1985 publication of Zindi’s book, and some of his hopes have materialised. Way back when, just two record companies possessed a monopoly on production, namely Teal Record Company, which became Gramma Records, and Gallo Record Company, whose local subsidiary became Zimbabwe Music Corporation. Today, several record companies have sprouted.

While there’s still an opportunity for growth in the industry, Zimbabwean music is easing itself back onto the world stage, and it all began decades ago with Mapfumo, Mtukudzi, Sithole, Susan Mapfumo, Majaivana and others. These musicians, propelled by the liberation war happening around them, laid the groundwork for generations to come.

For Zindi, that’s worth remembering.

“It's a very important thing for anybody to know their history, where they came from and where they're going now, especially with changes in technology,” he said. “I think it's important for the nation to know that.”