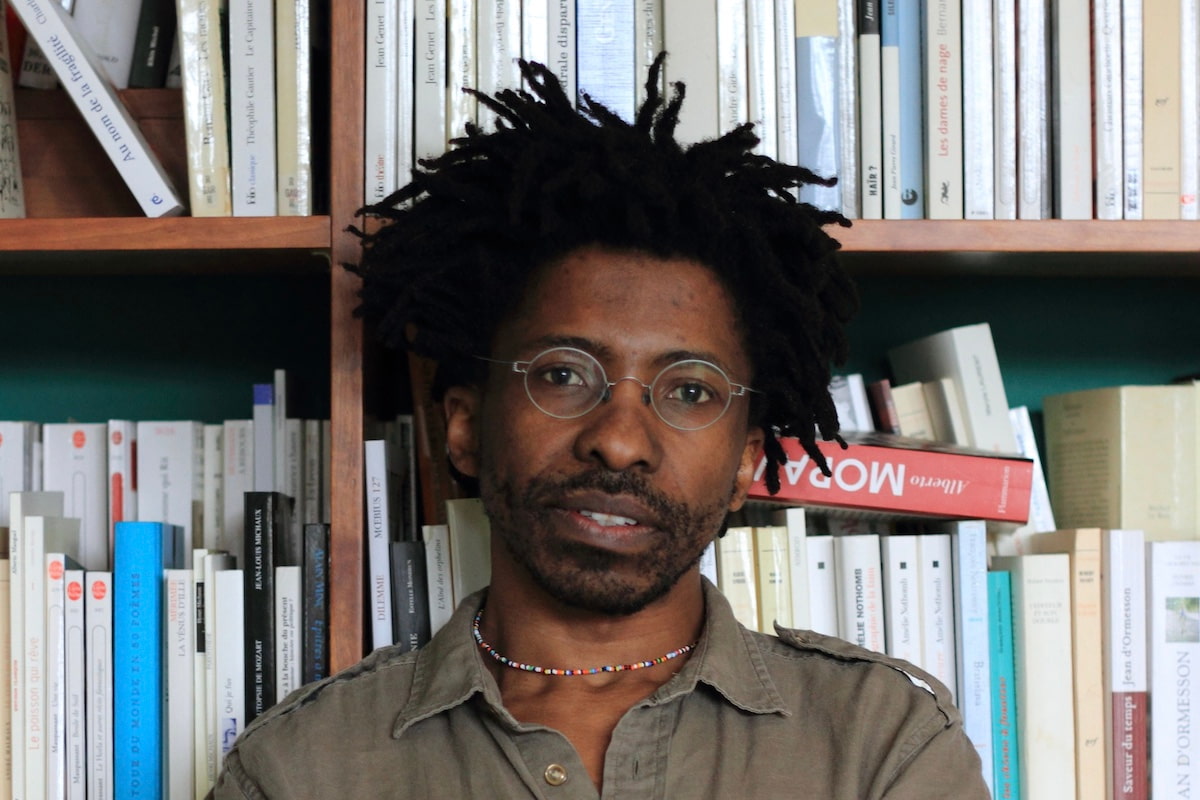

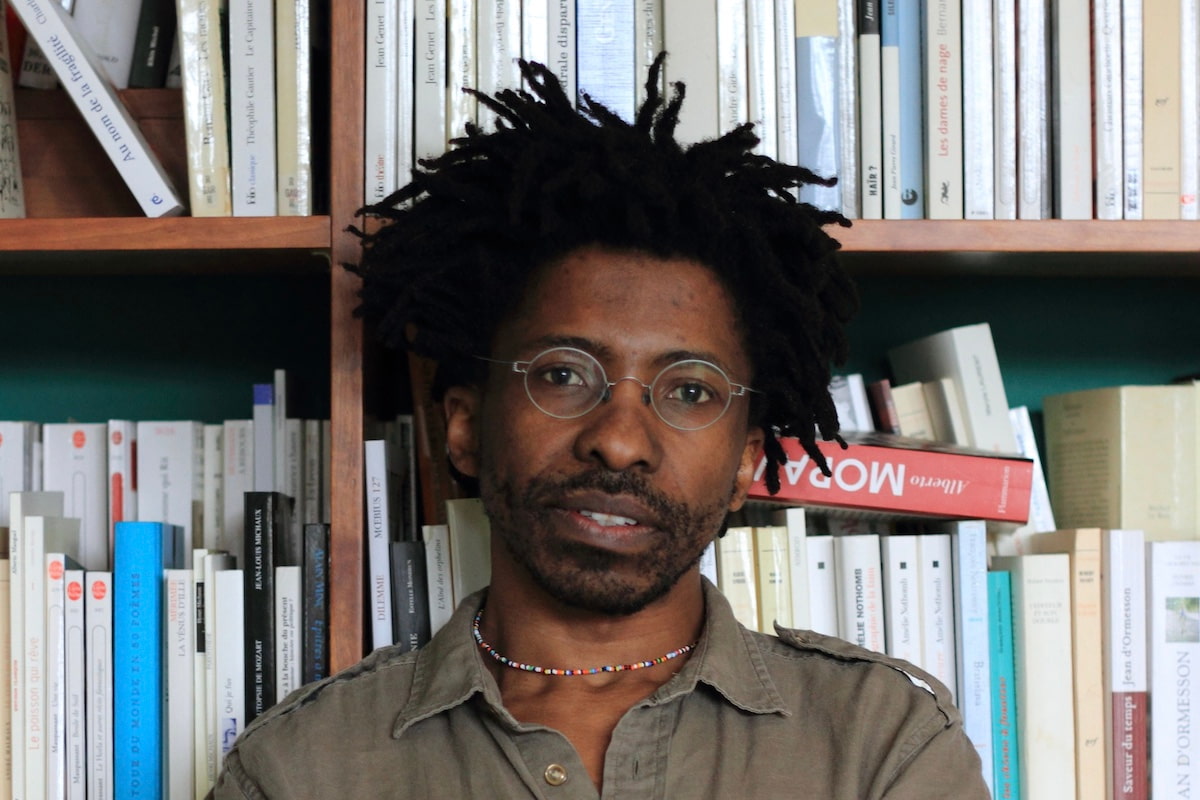

THE EPONYMOUS PROTAGONIST of “Shamiso” is unabashed, translucent in her vulnerability and endlessly hilarious. When you meet Brian Chikwava, the author, it’s easy to see why the last of these is front and centre. Over a Zoom call taken from the UK, where he relocated in 2003, Chikwava laughed constantly, whether to preface or punctuate his thoughts — funny, contemplative or otherwise — on his book, which was published on 28 August.

Although there are echoes of Chikwava in the book's titular character, Shamiso stands apart from the writer, wholly inhabiting a world of her own. The child of a political pundit, Shamiso lives in Harare, where she spends time with her beloved, eccentric Babamukuru Jimson, and their exploits constitute much of the humour in the book’s first act. She is on the periphery of her family, and Jimson, in advocating for her reintegration, comes to embody the role of her father figure, mentor and, ultimately, friend. Years later, she moves to the UK for school, where she meets George, the antithesis of Babamukuru. Where the latter is steadfast and reliable, the former is spontaneous and flighty. Shamiso is pulled into George’s vortex, all while she navigates self-discovery and life as an African immigrant in Europe.

Chikwava spoke to Landlocked about bringing the fierce Shamiso and the characters who surround her to life. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How has settling in the UK changed the way you write and think about writing?

Oh, now I write as a migrant, like people from the “shithole countries.” [Laughs.] It's a different way of writing, because you're writing from the margins. As a writer in Zimbabwe, you tend to be much more concerned with the political goings on in the country because they affect you so directly in a much more visible way than they do here. Here, it's issues of being in the diaspora and being on the margins and having to deal with the hierarchy that is imposed to manage certain people.

That comes through in both the protagonist of your first novel and now in the protagonist of “Shamiso,” which is your first novel in about 16 years. How does it feel to have put something out into the world after a decade and a half?

It feels good, but also, I feel like I should really kind of get over it very quickly and get on to the next thing, you know? My publisher loves to do all these publicity things. I do like going around, talking about the book and selling the book, but up to an extent. I think I should really, at some point, check out and go and do my own things, basically go back to writing. Because I should have written a book that, at least I hope, I don't have to go around selling myself. [Laughs.]

Fingers crossed.

Yeah, thank you.

Did you make a conscious decision to take a break after “Harare North,” or is that sort of just how it happened? What was happening in those 16 years?

It's just how it happened, really. I was trying to start a second novel, but I was really struggling with it. I just was not in the right place to write it, I thought, for a number of reasons. I discovered kind of weirdly this year that I've been struggling all these years with a gluten intolerance. I didn't know what it was. I just thought I had this mysterious condition. And it got progressively worse. I was struggling to get to the end of this one, “Shamiso,” and then the beginning of this year, that's when I had the breakthrough and discovered that my problem all these years is this thing. I thought I'd been bewitched by someone from Zimbabwe! [Laughs.]

So, how did “Shamiso” come to you?

Well, the idea came from basically wanting to write about Zimbabwe as a country, but also being able to write a novel where you've got a whole narrative arc that covers the history of the country. The scope of it is wide: Shamiso starts narrating it before she was born. I thought I needed to have everything that I feel is relevant to Zimbabwe as it is, as a new nation. So I had to start way back there and bring it to now, when a huge chunk of Zimbabweans have left the country and will become kind of a diaspora people, which is a phenomenon that came after the turn of the century. I also wanted to cover that. So in order to do that, I have to basically bring Shamiso to the diaspora to have her deal with the issues of the diaspora.

You said in an interview with The Massachusetts Review a few years ago that Yvonne Vera and Dambudzo Marechera are some of the writers who have affected you. Do you see their craft influencing the way that you wrote “Shamiso” or thought about writing this novel in any way?

It's probably unconscious in a way, because there are some things that I look at in “Shamiso” and think, “Oh, where did that come from?” My initial idea was to write about these troubadour musicians, the masiganda. I like that idea, but it is also a Vera influence. She writes about Bulawayo and South Africa absolutely wonderfully. But there was really not much in it there to develop into a story, which is why I ended up having Babamukuru Jimson as the only representation of that, and making something else with other elements of the novel.

With Marechera, that's difficult because he is almost inimitable. I've seen a lot of people ruin their work by trying to write like Marechera. It's almost something that you kind of admire, but don't want to really try to do because you will ruin your writing. It also requires a certain intensity of persona. You have to have a certain intense temperament, which I think I lack. [Laughs.]

Just from this conversation and from reading “Shamiso,” I'd agree. [Laughs.] “Intense” is not the word that comes to mind. On that note, I found the book just deeply funny in ways that I wasn't expecting. There were so many laugh-out-loud moments, like the whole interaction with the ice cream man, which just went on and on. But then you also have these darkly funny moments, like when Shamiso is in school, and she witnesses, at a celebration, the Education Secretary cutting into a cake that is in the likeness of an African woman. Why did you decide to write the book in that way?

A lot of the time, I find that when I write, whatever subject I'm dealing with, I need to give it a treatment that has these funny or comic tonalities, because that helps in a lot of ways to break through the seriousness with which you would otherwise treat a subject, and then it becomes a bit too serious. But also, humour has the advantage of breaking through a lot of things. You can easily deploy humour to deal with things that you'd not otherwise be able to talk about because they're divisive politically or otherwise. But when you bring humour into it, it is possible to handle things that are divisive without drawing a lot of fire.

Right. For Shamiso, it's a coping mechanism in some ways. She's obviously going through grief. I think identity is the theme, for me, that is most transparent. But grief is more opaque because she uses this veil of humour to deal with it.

That's quite good.

Is that a correct reading of it?

Yes. I mean, when I was writing it, I thought, I want the grief element to be right there, but I don't want to spell it out or overcook it; otherwise, you can really go down this slippery slope where you end up somewhere that is a bit dubious. One thing that I remember thinking about was that she's actually someone who has suffered a lot and is grieving on so many levels, but I don't want that to be the defining thing about her. I want her to be someone who is strong.

I remember when my publisher asked, “What is your book going to be?” and I thought, well, basically what I wanted to do was to write like someone who is a kind of superhero, not in the comic sense of Marvel, but someone who is extraordinarily strong and can go through things that normal people can't. I wanted her to be that because if I didn't, the danger was turning her into an object of pity, and I hate turning my characters into objects of pity. From my experience living here, that is something that is at the forefront when it comes to migrant communities. If you're a migrant, I mean, you're either problematic or you're acceptable only if you're an object of pity, and I didn't want to do that.

Shamiso is far from an object of pity. In some ways, she's almost too strong. I wanted her to have a mental breakdown or something! She really powers through. My favourite thing about the book is how you play with gender pronouns. To hear “Shamiso” say so blatantly that there are no gender pronouns in Shona is something I'd never even considered. Talk to me about the choice of using “they” pronouns in the two different ways: to show respect and to represent gender fluidity.

It's quite an interesting thing. I remember when I was writing, I wanted to deal with the more queer elements of the novel. I thought, okay, how do I write this? I could just write it the way everyone writes it in London here, in which case there will be no distinction between what I do and what any other British writers do. But also, there is actually a genuine thing to do with language, which is that Shona, Ndebele, the Bantu languages, they're structured completely differently grammatically compared to English.

If I'm going to write about something like gender identity or sexuality, to use the English language as it is is problematic because it is a language that actually produces those binaries. But Shona and Ndebele are very different in that you can tell a story without really mentioning someone's gender, and no one would be able to tell what gender they are unless they know how they are related to everyone else. Creatively, I think that is quite fascinating. I decided I just have to do this because it speaks to not just the whole idea of gender identity and sexuality, but also the idea of respect in Zimbabwe — “them” and the like. I could bring it into collision with how that is used here and create something much more interesting that way. I couldn't resist that.

Do you think it worked?

I think it worked, yes. I mean, I needed to strike a balance between making a political point and being comprehensible, which is kind of a fine balance. But I tried my best to tell a story and still be readable.

Do you think you could have written a book like this in this specific way while living in Zimbabwe? Or do you find that being based in the UK, removed from the environment of homophobia and transphobia that exists in Zimbabwe, enabled you to explore those themes?

I don't think I would have been able to write like that in Zimbabwe. The reason being that in Zimbabwe, there are a lot of issues with homophobia and transphobia. Those are issues across a lot of Africa. But also, I know that when you kind of look at it in detail, you find that those phobias tend to be very intense coming from, say, places like the church. In Uganda, it's actually worse. You can see that it's being driven by the evangelical churches that are from the US. A lot of people are like, “This is our Africa. These are our values.” It is fine, yes, but a lot of this is inherited from our colonisers and the language you speak. It is those European languages that produce those binaries and make it much easier to accept. The idea that homosexuality is alien to Africa is just complete nonsense.

I thought, if I'm going to write a book, I'm writing from here, but also in the diaspora, where we have to face up to decoloniality. That's really the struggle. If I'm going to write a book, I need to speak to that. It's much more urgent for me from here than it probably would be in Zimbabwe, because in Zimbabwe, I'll have to deal with a different set of priorities, right? But here, it's much more urgent that I speak to that and make it clear that there are ways of thinking. The African languages themselves produce different ways of thinking or different ways of seeing. The European perspective is not universal and should not be. There's nothing wrong with it, but it's just that it cannot be allowed to take centre stage at the expense of other perspectives that the Europeans could learn a lot from.

I think Shamiso is also very aware of that. I found it surprising that, having come from a very conservative country, Zimbabwe, and being the child of a member of parliament under Mugabe, she almost doesn't bat an eye when she realises George has this different way of presenting themself that maybe she hadn't seen in Zimbabwe. What does that say about her and the way that she thinks about the world?

She's come to England in search of herself, and from that moment, I think she, maybe subconsciously, makes that decision. She's willing to meet difference, because that's a decision she has chosen. She has chosen to come to a place that is different, where she will have to deal with difference, and she will have to be open to that. If she is not, then everything falls apart right there. And it's much more interesting to be open to the world, right?

Does Babamukuru Jimson's own social standing as almost an outcast influence Shamiso's worldview?

I really love this idea of an outsider. I mean, Shamiso feels that, but also, what is important is that without Jimson, her life takes a completely different turn. But because Jimson is an outsider in many ways, and also because of his place within the family, he manages to say to Shamiso's father, “This is your child. Look after your child.” Because of that, she's taken into the family, and she, in the early years, finds a lot of strength in Jimson, not only because he is the person responsible for bringing her into the family, but also because he gives her a sense of stability. He's the only one who values her, and she begins trying to learn what he's doing, like the sculptures and things like that. She inherits a lot of that. It's not something that Shamiso would have done consciously, thinking that she was going to be an artist; it just happened, and she was shaped by that.

When she comes to the UK, that's when she discovers that there's an element of Jimson in herself, an element of the outsider. Even in her first encounter with other Africans here, when she's taken to London for the first time, she almost puts herself in Jimson's head, the way she's looking at these people. She becomes Jimson there.

I love the detail of her cat being named Babamukuru.

I thought I had to do that for the simple reason that she lost Jimson and never really grieved properly. I thought I needed to give her proper closure with Babamukuru. At the end, the cat dies rather brutally, but this time, she manages to actually give him a sendoff and say goodbye.

At this point, she's also confronted with Nishta and Gabriel's divorce and the impermanence of her relationship with George, who, unlike Babamukuru, comes in and out of her life as they please, which destroys her. At the end, she realises that George is happy with who they are and where they are. She finds closure within herself, and she decides to leave the UK. What is she going back to when she returns to Zimbabwe?

You see, I didn't really think that one was such a big or important question for that ending. Why? Because what I needed to make the point was the fact that, for Shamiso, after university, she becomes an illegal migrant, and [might take precious green cards] from lots of other migrants who might choose to stay for years and years. She actually makes this decision to leave, and it is very important for her to leave. It's not just a choice that she makes as Shamiso, who is like, “Okay, I have no papers,” but as someone who has become aware that where she is, Europe, is a place where her lived reality is more dictated by the languages that she speaks, and a real liberty or freedom should mean escaping that, and she has to escape that. That's the point. She knows she has to go into another way of seeing the world.