THE SHORT STORY “Plumtree: True Stories” in Yvette Lisa Ndlovu's “Drinking from Graveyard Wells: Stories” opens with ants crawling out of a man’s penis because he has slept with someone’s wife. Readers learn that while this might be surprising, it is not unique. “Fixing” one’s wife, Ndlovu writes, “was what you did when you married a beautiful woman. If any man but you tasted your wife’s sweetness, that intruder would receive a nasty surprise on his way out.”

The story continues in this vein, detailing a series of circumstances interconnected by grave or downright horrific things happening to women in the name of “tradition” or chivanhu, highlighting the inherent prejudice of the Zimbabwean patriarchy. A line from the tale, “What men cannot do or understand is evil,” is a reference to varoyi, women with magical abilities who are often villainised.

But it is not just men who are at fault; women themselves, Ndlovu shows us, can also perpetuate injustice, upholding patriarchal values by condoning and participating in rituals that violate women, rituals like virginity tests and genital mutilation, the latter referred to as “the pulling.” “Plumtree” closes with retributive justice delivered by the feared magic: an uncle attempting to rape his underage niece is abruptly struck by lightning and dies instantaneously. A fitting ending for a harrowing read.

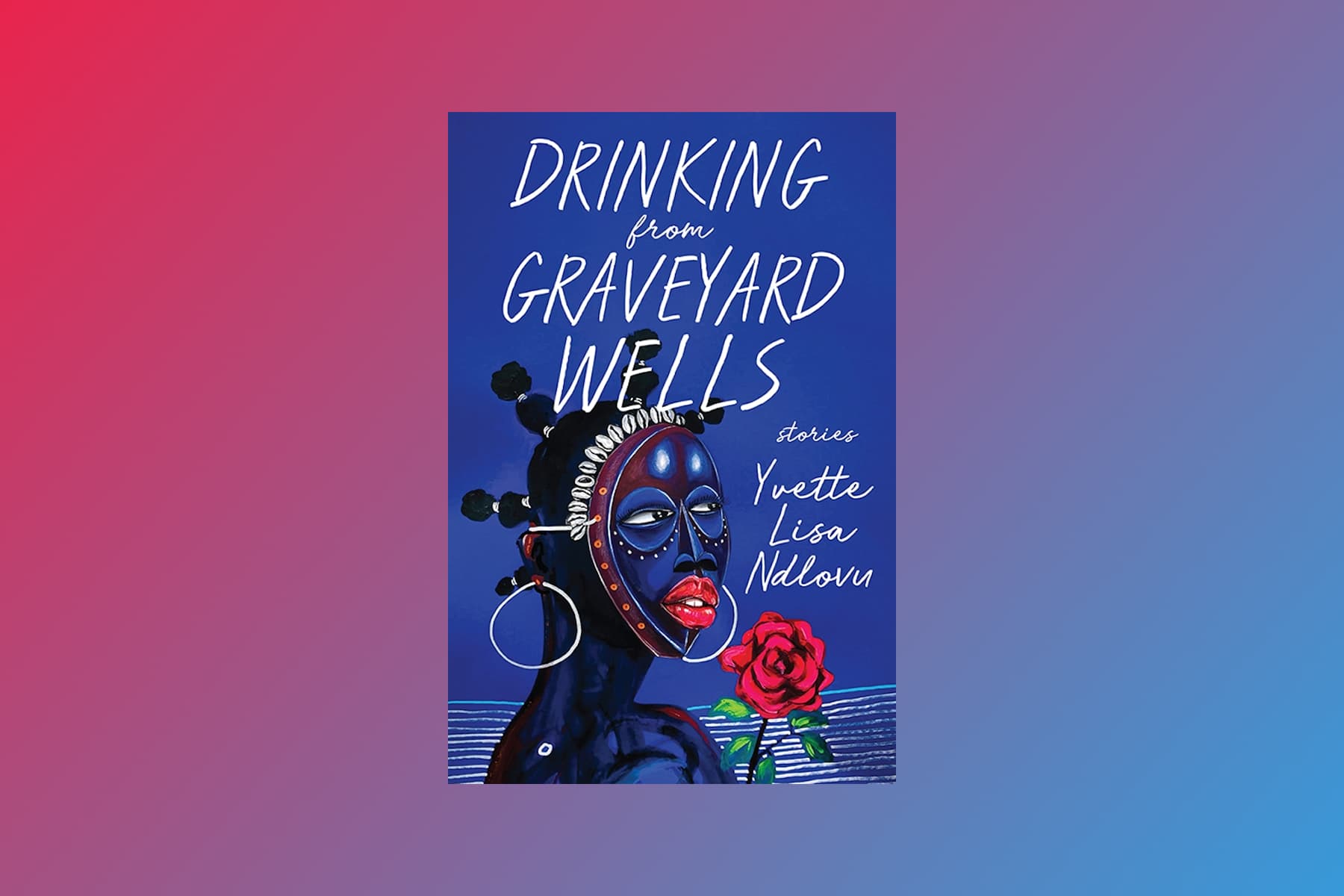

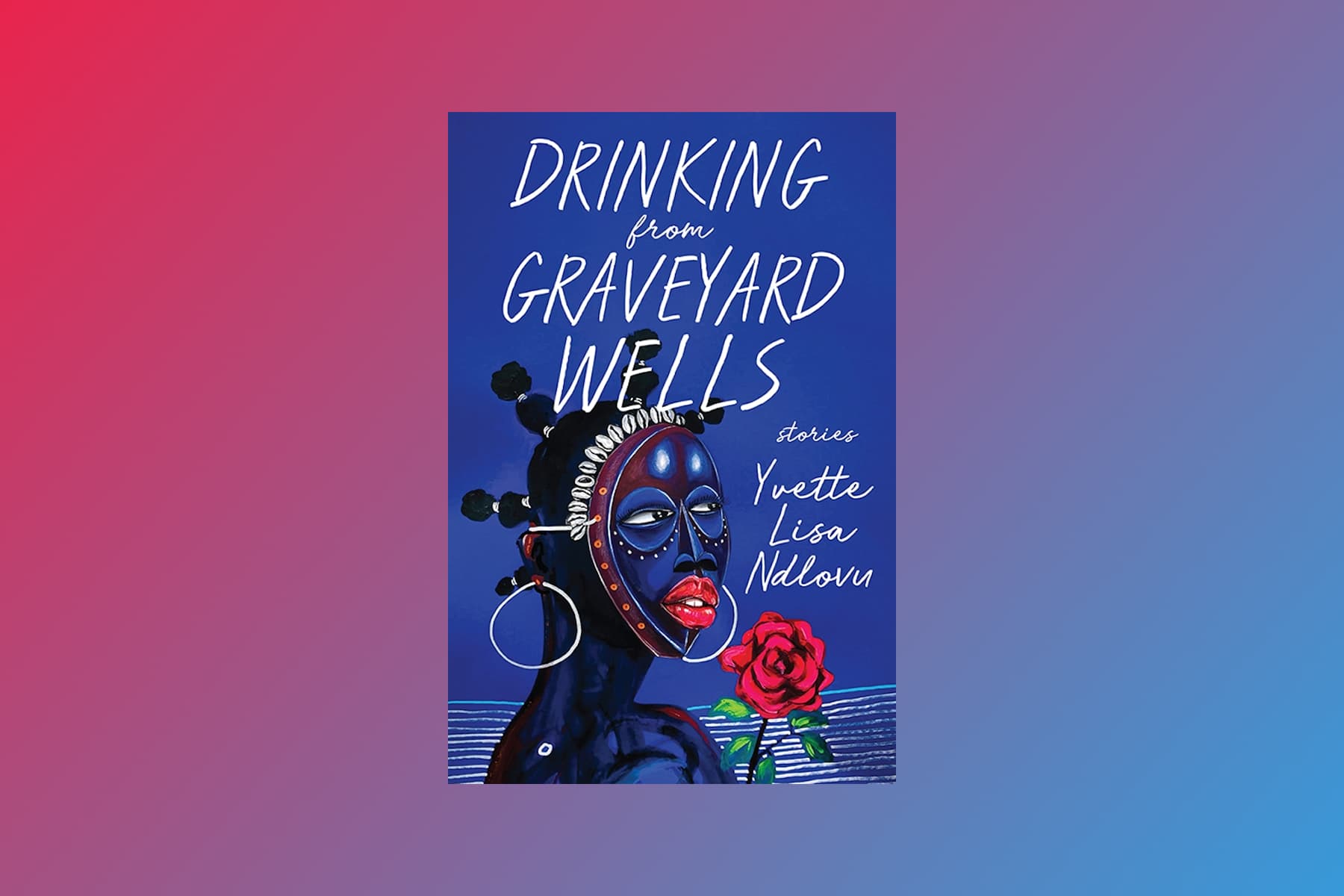

Zimbabwean folklore, which often features fantastical and supernatural elements, has often been accepted as a lived reality. Tales of kuroyiwa and vadzimu are understood to be a core tenet of the metaphysical — not just myths and legends, but ways of interpreting illogical occurrences in the world. Magical realism, I’d argue, is therefore a suitable genre for accurately conveying the facets of a typical Zimbabwean's life. In her debut short story collection, published in 2023, Ndlovu takes charge of the genre and, in her capacity as a self-proclaimed sarungano, a teller of stories, masterfully spins 14 fictitious tales that are distinctly and unapologetically Zimbabwean. She treats mysterious occurrences as innate elements of daily existence that require neither introduction nor explanation. She writes of stories that, at first, appear incredible and fantastical in nature, but upon further consideration, could indeed be true. For those Zimbabweans who grew up hearing stories like those in the collection, fiction is truth.

Magical realism is marked by the existence of fantastical elements in an otherwise ordinary world. One might think of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez as the quintessential novel of this genre, with its incorporation of preternatural elements throughout the novel. In the African literary canon, Ben Okri's work stands out as the paradigm of magical realism in the post-colonial landscape.

She treats mysterious occurrences as innate elements of daily existence that require neither introduction nor explanation. She writes of stories that, at first, appear incredible and fantastical in nature, but upon further consideration, could indeed be true. For those Zimbabweans who grew up hearing stories like those in the collection, fiction is truth.

While Ndlovu is a relatively recent newcomer to the literary world inhabited by the likes of Marquez and Okri, she sits comfortably alongside them. Still, in “Drinking from Graveyard Wells,” she does not restrict herself to the genre, instead also exploring speculative and realistic forms of storytelling. The result is a gut-punching exhibition of the range of Zimbabwean experiences rooted in a storytelling tradition of folklore, myths and legends. It is an astute reflection and subtle commentary on the zeitgeist of post-independence Zimbabwe, dancing between the real and the otherworldly.

In “Turtle Heart,” the writer takes the approach of a typical ngano, or folktale, with a tie to reality. In the story, a king refuses to give up the throne after gaining power and eats turtle hearts in hopes of living longer and thus extending his reign. The story concludes with, “Even now, when you visit the island, you can still find his skeleton there sitting on the big seat,” offering fact for fiction.

Politics and its consequences feature as prominent motifs in Ndlovu’s stories. The author uses ordinary human existence to highlight the negative implications of corruption and immigration. She also writes lengthily about the Zimbabwean diaspora and showcases the inherent plights of being an immigrant, including the degradation and horrors of the immigration process.

In “Home Became A Thing With Thorns,” a grotesque naturalisation process requires that a key component of an immigrant’s existence be taken away as a sacrifice. To become a citizen, Jabu, who loves to create art, has his eyes taken away, leaving him depressed. The story captures the often humiliating immigration policies and the sacrifices people are willing to make to integrate into a new society. Jabu and other characters long for home, that is, Zimbabwe, and think back on it fondly, but they know they can never return because home has also become a hostile environment. Ndlovu writes: “No price is too big to never see the shavis again,” referring to War, Disease, Poverty, and Corruption, which, in the story, are sentient deities intent on “ravaging [the narrator’s] homeland.”

Another underlying theme in the collection is society and how it upholds longstanding traditions and values. The collection features both good and bad traditions — traditions that reinforce the importance of community, and traditions that perpetuate harmful practices, which women face the brunt of.

And then there is the question of tradition, the ills of which Ndlovu tackles in “Red Cloth, White Giraffe.” When a woman dies from kidney failure, a death that could've been prevented had the country had better healthcare, her family refuses to bury her because her lobola, or bride price, has not been paid in full. The woman observes from beyond the grave as her headstrong relatives make irrational demands of her grieving husband. The funeral, meant to be a time of mourning for the community and family, becomes an opportunity for the relatives to gain money from the heartbroken husband.

In contrast, “Water Bites Back” and “Three Deaths and the Ocean of Time” portray tradition more favourably, emphasising the value of intercessors who are well-versed in breaching the divide between everyday existence and the mystical and supernatural world. In “Water Bites Back,” a minister attempting to build a bridge does not convene with the guardians of water, resulting in disastrous consequences. In “Three Deaths and the Ocean of Time,” the main character seeks counsel from Gogo Pentshisi, a woman knowledgeable in “African science,” on how to get to the Zamani, or the past, where her ancestor has been calling her. The character successfully travels back in time, returning with invaluable knowledge.

In keeping with the Zimbabwean oral tradition, “Drinking from Graveyard Wells” weaves a network of narratives that stretch across the country and beyond its borders, rendering mythical creatures and spirits believable and tangible. Ndlovu’s stories move seamlessly between death and life, reality and the supernatural, eradicating the veil that separates fact from fiction.