YOU MAY HAVE HEARD the story while crowded in a tent, peeking over a bunkbed in the low light of night or maybe huddled around a crackling fire. It’s a classic camp legend, or so they say, and it formed the basis of Tanaka Chiriga’s second short film, “Mrs. Willow,” an unsettling horror that follows protagonist Benny on a retreat-gone-wrong to the Chimanimani mountains.

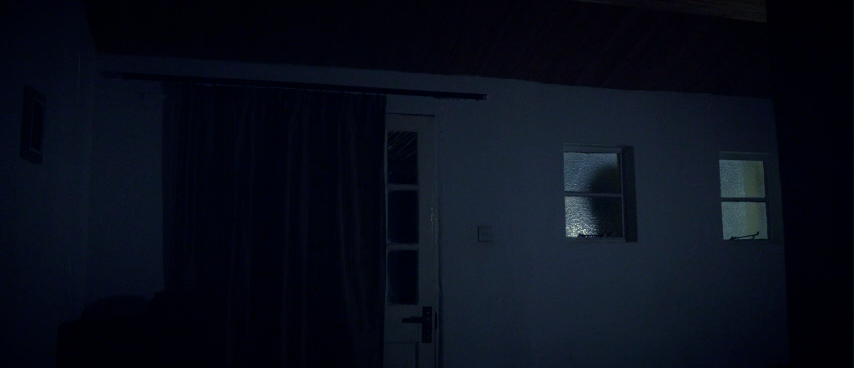

One of the many versions of the ghost tale goes like this: During the Second Chimurenga, in the mountains of Chimanimani, then called Melsetter, liberation fighters entered Mrs. Willow’s home looking for her husband, a Rhodesian soldier. When the mother of two told the fighters that she didn’t know where he was, they locked her up in her shed and set it ablaze. As the flames engulfed her, she watched through a window as her children screamed for their dying mother and fled. Mrs. Willow’s ghost, they say, still roams the mountains looking for her children, ready to haunt those who inadvertently summon her. This is the situation protagonist Benny finds himself in after nicking a toy — a rocking horse — that belonged to one of Mrs. Willow’s children.

Chiriga, a 35-year-old Harare-based filmmaker and motion graphics designer, first heard the story of Mrs. Willow in 2003, while at a Grade Seven team-building and leadership camp at Outward Bound in Chimanimani, the small town in the southeastern region of the country. The story stayed with Chiriga for years, aided no doubt in part by the eerie events that took place during the trip. These events, by Chiriga’s recollection, included a torrential downpour that led to the boys being woken up in the middle of the night and led, on foot, through the dark, away from their lodging in the mountains to the base camp. A day later, the rain having cleared, the boys returned to the mountains, where their counsellors told them the ghost story. The following morning, as they continued up the mountain, the kids passed a cairn. There lay Mrs. Willow.

A spooky ghost story made tangible by an uncanny freak weather event and an alleged burial site? Chiriga knew he just had to revisit it someday. And so, his 2025 short film, “Mrs. Willow,” came to be, somehow more hair-raising than the camp tale itself, or the supposed war-era events that inspired it. The short has made the rounds at various festivals, landing official selections at the Matatu Film Stage and the SA Horror Fest, as well as a nomination for Best Horror Short at the Indie Short Fest.

This isn’t Chiriga’s first film. In 2018, he released “Bhizautare RaArthur” (“Arthur’s Bicycle”), a 17-minute short about a young man whose suicide throws his family into a tailspin. Chiriga is currently working on a film about makorokoza, the artisanal miners he encountered while digging for gold on a family claim in the village of Chakari. He spoke to Landlocked about the spontaneity and challenges of making “Mrs. Willow,” which will soon be available to the public, on a shoestring budget with just his partner, Melissa Savary.

.jpg)

When you heard the story about Mrs. Willow, did you have a sense that it was something that had actually happened, or that it was just one of those campfire stories that your counsellors were telling you?

It felt like it happened, because there was a lot of historical context —

It was based on the Liberation War. The real thing.

Right. And even now, when I'm doing history research for my own joy, a lot of those border areas, especially with Mozambique, were hot zones [of the war]. So now, if you think about it in retrospect, that's when it starts to make a lot of sense that in Chimanimani, a lot of these things would be happening. It adds this extra tension that evolves from the racial tension of it, that it's these Black rebels and this white woman, and there’s this conflict that’s happening between them. It’s an interesting dynamic because, in our class, we had Black students and white students as well.

So much to unpack there. The racial element of it is very interesting. There’s something almost spooky in that it’s an image of a white woman being brutalised by indigenous African soldiers in a time when Zimbabwe is fighting for its freedom. It’s almost like the script is being flipped to show these Black Zimbabwean men as barbarians in a way. I’m very curious about the origin of that story and what its purpose was, and who came up with it.

Looking back at it, in a very untamed place like Chimanimani, you want to instil a kind of, I wouldn’t want to call it fear, but a boundary within the students, to be like, “There are things out there. We won't necessarily say there are dangerous things, but we can give it to you in a concept that you can understand.” So that could have been the origin of it.

Also, I think within those places, the ghost stories aside, there are lots of stories of people during the liberation struggle and the war, where there were skirmishes that happened and brutalisation on both sides. I'm not a historian, and I haven’t really dug deep into it, but war is never going to be a straightforward thing. There’s always going to be a brutal nature to it. That is already a horror story as well. So it’s only natural that scary stories like that would emerge within that context.

You knew that you wanted to revisit the story of Mrs. Willow in some way. Why choose film?

My creative journey started off in music, and I thought that's what I was going to be doing, but it just didn't work out that way. My brother went to film school, and he had started working on projects with his partner in America. I was still working on music, and I had this whole collection of songs. This was the era where people would make an album, and every single song on the album had a visual accompanying it. So my brother was like, “It would be great if we did that as well.” He's based in New York, and two or three months before he was set to come this side, I lost all the files, so we pivoted, and we decided to make a movie. That's when “Arthur’s Bicycle” came to be. That was the first foray into making a film. We sent it out to some festivals and got some decent play.

Fast forward, several years later — my partner, Melissa [Savary], who is “Mrs. Willow” in the movie, is based in Canada. She’s into horror. When we were talking about it, horror stories naturally came up, and then Mrs. Willow came up, and this all came around the same time she was planning to come and visit. And it was like, You know what? You’re coming to visit, and we want to go and hang out in the mountains. I had just gotten a new camera, and I was like, “Why don’t we just make it into a movie?” That whole “Arthur’s Bicycle” process showed us that a movie doesn’t have to be super planned out; we start with something, and we build it until we have a structure or a script or at least a storyboard of what needs to happen, and then we move from there.

You are a creative motion graphics designer by trade, and you’re working with corporate clients a lot of the time, whereas film, I think of as sort of the opposite of corporate. Sure, there’s a business behind it, but filmmakers tend to sort of stray from that. How do you hold those two things in balance?

They are completely different workflows and also thought processes. What helps me with motion graphics specifically is that because I’ve been doing it for such a long time, it’s almost second nature. I'm able to remove myself, so it doesn't drain me creatively. I'm using my creativity to generate things, but the drain from making a film is a different type of drain, because you’re almost leaving yourself on the project that you’re making. It’s not that difficult to separate the two, and sometimes they actually even complement each other, because you're always talking to people. When you’re talking to a corporate client, their main thing is to sell something, but to be able to sell something, you have to make it compelling. And when you're making a film, you want it to be compelling.

I don’t watch horror movies at all. I’m a scaredy cat, but I obviously watched your film. I do know, though, that the use of a video camera is quite a common motif in horror movies, like in “The Blair Witch Project” and “Paranormal Activity.” It shows up in your film, too. Was that a recall to that type of horror filmmaking?

Definitely. The funny thing about it is that a lot of people will look at “Mrs. Willow” and be like, “This person is absolutely into horror movies.” I’m not really into horror movies. So when I was now approaching this horror, I took it as a challenge to use some of the [horror] devices. It was also a part of the brainstorming where Melissa was showing me a documentary that she had worked on, and it was giving me “Blair Witch” vibes. I thought: Let’s add that in there. Oftentimes, my process doesn’t come from a brainstorming session; it comes from everyday life.

.jpg)

There’s a detail I was curious about that I'm sure has no real bearing on the whole story. But when Uncle Benny first arrives at the house, he’s sitting on the couch, and then he picks up a magazine. It's a Vanity Fair issue from 2006. Why that magazine? The camera lingers on it.

What’s funny is that the magazine was in the accommodation we went to. We ended up deciding to put it in because the cover has a picture of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Al Gore. And why it's so funny now, when you look at it, is, would these two people actually pose for Vanity Fair in this day and age? I'm happy that you picked up on it, because I like doing that, throwing in little nuggets like that. I have a whole bunch of them. And that one specifically was because during the time when we were filming, I think [Kennedy’s] confirmation was about to happen. So it was big news. But I guess, if you’re releasing the film in Zimbabwe, people don’t care who that is, you know? It's a throwaway thing, but it also speaks to the overall theme of the movie, which is about how times have changed. Benny, he’s in this house, but it was a white woman's house, and he wouldn’t have been able to be in that house during that time. So all these things kind of just form and meld.

There’s no speech in the film, which added to the eeriness of it. We see communication through text. We hear Uncle Benny grunt a couple of times. But there's no speech. Why?

So for two reasons. The first was a technical thing. There were just two of us, and I had sound equipment to record dialogue. But we only had a few days. We wanted to get as many shots as we wanted. The most important thing was to focus on the framing, to try and get the lighting as good as possible. If we threw sound into the mix when there were only two of us, it would’ve been one person behind the camera at any given time. So now I'm running the camera, running sound. If there are only two characters, who would Benny be talking to?

The second thing is that it doesn't serve the story in that way, because it’s almost like an internal reflection for this character, and you're kind of experiencing it with him. You can put yourself into Benny's shoes. “What is he thinking?” If a character tells you, “Today is hot,” you’re going to be like, “That character thinks today’s hot.” But if they look at the sky, you don't know, do they think today is a beautiful day? Are they thinking about someone? Are they thinking about the future? Are they thinking about the past? It makes it a more active experience, right?

It’s also a gamble, because now, with people’s attention spans — people watching 30-second TikTok videos — if there’s no dialogue happening, it's a bit of a gamble. But if people decide they want to watch it and take the time to, I hope they find it almost like a meditation as well, just to slow themselves down. When I was watching the movie from front to back, I would always find myself watching it silently, and almost walking through the journey as well, versus it being an experience where you put on a Netflix show, and you let it run in the background while you do something else. I wanted people to be more active and to pay attention, because there's enough content out there that you don't need to pay attention to; it's a nice experience if you do pay attention to it.

The point about the technical limitations of a two-person film crew and how that translates into how audiences experience the film is an interesting one. Do you feel that, in some ways, that has the potential to produce a more, I guess, pure art form, versus having a limitless budget, all the equipment that you need, a huge crew?

In terms of purity, I wouldn’t say that it’s dependent on what you use to create what you're creating. I think it's more so the intention behind what you're doing. The intention for Mrs. Willow could have been to make it into a product that I can sell to make money. That takes away from the art of it, even if it’s just two people. Or you can have someone who is like, “My vision is so powerful and so strong that some of the things that I need require a lot of money.” For instance, if the director says, “This person has to fall through space and then go underground in the same shot,” it’s going to require some money and some budget. But their reasoning for it is that it’s a transformative thing if you see it on the big screen, you know? I don't think that a skeleton crew kind of operation makes it art automatically; it's more so, “Why are we doing it?”

For sure. I obviously don't want to romanticise not having money and resources, but there's almost a beautiful poetry in making do with what you have, especially for a lot of Zimbabwean filmmakers, where there's not a lot of funding for arts and culture. There's poetry in being able to make do in that way.

I know what you mean. I spoke to someone who had seen the trailer, and he was talking about the projects that he wants to do, and it was a very ambitious project, right? It’s good that he's thinking that way. But I think the differentiator is: are you actually going to make films, or are you just going to stay in ideation? Can you creatively problem-solve all these big ideas with what you have right now? Because ultimately, that's what matters. That's something that a lot of people, especially here in Zim, could benefit from. If you can do something with bare bones, that means that now you're exercising that muscle, so that when you do have the resources, you know you can definitely execute. You’re developing a system in which to tell that story effectively, and I think that's the real kind of gold mine for creatives.

We talked about the fact that you’re not into horror movies, but you took the step to make this film. Your first short film, “Arthur's Bicycle,” is not horror, but it deals with really dark themes. Do you find yourself drawn to psychological films in that way?

I'm happy you say that “Arthur’s Bicycle” has a dark theme to it. Ultimately, it’s a story about Arthur, who had an affliction, and he was feeling depressed, and he didn't know how to deal with it, and then he took his life. What was left was a whole bunch of confusion for everybody. It's just really unfortunate that he wasn't able to get the help that he needed. It also echoes just what happens everywhere in the world, where people still, to this day, surprisingly, have a very weird relationship with mental illness and what it means.

Yeah, and even Uncle Benny seems to be struggling with his mental health, so that's a throughline as well.

The theme of people’s inner workings is something that I like to explore, because I have had my own issues. I've been very depressed at times in my life, and growing up in a place like Harare, even when I went to stay with my grandmother in Masvingo, people don't really look at it that way, as something you can help someone with. That's why I like to lean towards telling stories that involve something like that, even with my music.